δ

THE PERSONAL AS THE POLITICAL

Women of today are still being called upon to stretch across the gap of male ignorance and to educated men as to our existence and our needs. This is an old and primary tool of all oppressors to keep the oppressed occupied with the master’s concerns. Now we hear that it is the task of women of Color to educate white women – in the face of tremendous resistance – as to our existence, our differences, our relative roles in our joint survival. This is a diversion of energies and a tragic repetition of racist patriarchal thought. Simone de Beauvoir once said: “It is in the knowledge of the genuine conditions of our lives that we must draw our strength to live and our reasons for acting.” Racism and homophobia are real conditions of all our lives in this place and time. I urge each one of us here to reach down into that deep place of knowledge inside herself and touch that terror and loathing of any difference that lives there. See whose face it wears. Then the personal as the political can begin to illuminate all our choices. (Audre Lorde, The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House, 1984.)

POSTULATED / INCARNATED

The nature of fascism can be characterized as the inverse of democracy. On both sides, it is a matter of the power of the people. But whereas in democracy the people itself is postulated, in fascism it is incarnated. I mean “postulated” here in a Kantian sense: a reality of the people must be thought, or represented, in order to serve as a rule in the conception of politics. And I mean “incarnated” in a phantasmatic way since neither an individual nor any other alleged entity (race or nation, for instance) would be able to incorporate a people. In this sense, fascism is premised upon a rejection of the democratic postulate: it rejects democracy’s will to regulate itself in accordance with an idea of the people that itself responds to the visionary or ideal character of this idea and, in its place, substitutes its own decision to affirm the tangible reality of the people. It is clear that the democratic postulate involves a fragility that is constitutive: in one sense, democracy itself declares that, in order to have a functional democracy, what it names is not, and must not, be made present. Conversely, fascism involves a force that is constitutive: it affirms itself as the only real, almost immediate, expression (be it in the immediacy of a figure or symbol). Democracy nourishes a fundamental need of institutions, laws, and rules. On one side, the complexity of institutions and rules increases the fragility of democracy. So when the concrete material and spiritual situation of a country seems to expose that fragility as a serious or even pathological weakness (regardless of the actual causes), we can see how it is that the fascist reaction arises.

But that does not mean that fascism arises, always and everywhere, under the completed figure of an armed hero or even of a catchy slogan. In fact, there is something old-fashioned about what such images evoke today. Contemporary sensibilities are more focused on a cinema verité or reality TV depiction of the “common people” or the “middle class.” There are many reasons for this, which I will not analyze here, but all of them have to do with a kind of general de-symbolisation that goes hand-in-hand with the general technological and cultural connectivity of society. But the fascist motivation remains the same even if it is no longer necessary to show the fasces of the lictor, the memory of which has, in any case, been lost. The meaning indeed remains the same: the lictor accompanies the high- ranking magistrate whose orders he is ready to execute. A power of execution without delay combined with the prestige of an immediately perceptible authority, this conjunction of material and impassioned forces seems to guarantee total compensation —active, recognizable, and participatory— for what democracy no longer seems capable of ensuring.

We must only add the following: on both sides, those of democracy and fascism, the powers of techno- economic domination are very much at ease. In democracy, they can rely on the weakness and complexity of institutions and rules; as regards fascism, they have no difficulties tying their own aims to it. But when the material situation darkens, the first becomes prey for the second, because the people rejects its postulation to demand the immediate satisfaction of its needs and its phantasms. In the long run, the people also ends up suffering from what fascism imposes on it. But that takes time… and it also depends upon whether the people is capable of entering into the exercise of the postulation such as I have characterized it here. This exercise is difficult and calls for a certain kind of virtue to resist the appeal of idols. This virtue is what we must try to cultivate in democracy. (Jean-Luc Nancy, Neofascism, LA Review of Books, 2019).

ON TRANSVERSALITY

What is Foucault trying to say in the best pages of The History of Sexuality? When the diagram of power abandons the model of sovereignty in favour of a disciplinary model, when it becomes the ‘bio- power’ or ‘bio-politics’ of populations, controlling and administering life, it is indeed life that emerges as the new object of power. At that point law increasingly renounces that symbol of sovereign privilege, the right to put someone to death (the death penalty), but allows itself to produce all the more hecatombs and genocides: not by returning to the old law of killing, but on the contrary in the name of race, precious space, conditions of life and the survival of a population that believes itself to be better than its enemy, which it now treats not as the juridical enemy of the old sovereign but as a toxic or infectious agent, a sort of ‘biological danger’. From that point on the death penalty tends to be abolished and holocausts grow ‘for the same reasons’, testifying all the more effectively to the death of man. But when power in this way takes life as its aim or object, then resistance to power already puts itself on the side of life, and turns life against power: ‘life as a political object was in a sense taken at face value and turned back against the system that was bent on controlling it’. Contrary to a fully established discourse, there is no need to uphold man in order to resist. What resistance extracts from this revered old man, as Nietzsche put it, is the forces of a life that is larger, more active, more affirmative and richer in possibilities. The superman has never meant anything but that: it is in man himself that we must liberate life, since man himself is a form of imprisonment for man. Life becomes resistance to power when power takes life as its object. Here again, the two operations belong to the same horizon (we can see this clearly in the question of abortion, when the most reactionary powers invoke a ‘right to live’). When power becomes bio-power resistance becomes the power of life, a vital power that cannot be confined within species, environment or the paths of a particular diagram. Is not the force that comes from outside a certain idea of Life, a certain vitalism, in which Foucault’s thought culminates? Is not life this capacity to resist force? From The Birth of the Clinic on, Foucault admired Bichat for having invented a new vitalism by defining life as the set of those functions which resist death. And for Foucault as much as for Nietzsche, it is in man himself that we must look for the set of forces and functions which resist the death of man. Spinoza said that there was no telling what the human body might achieve, once freed from human discipline. To which Foucault replies that there is no telling what man might achieve ‘as a living being’, as the set of forces that resist. (Gilles Deleuze, Foucault, 91-93, University of Minnesota Press, 1988.)

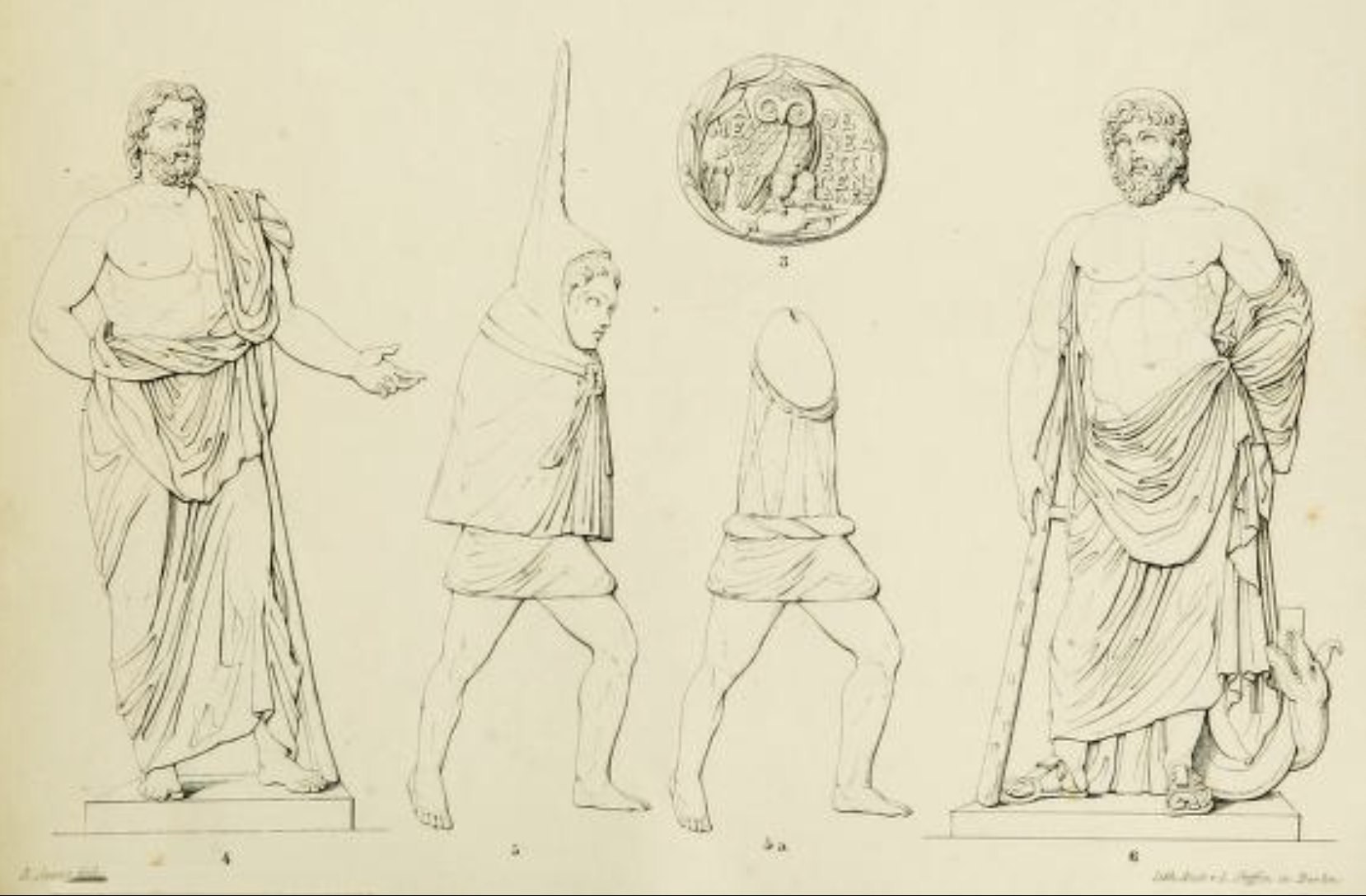

THE ACCOMPLISHER

An old auction catalogue from the 19th century revealed that at 1:30pm of 19 March 1867, three artefacts from Anafi from the Collection A. Raifé were sold at an auction in Paris at the Hotel des Commissaires-Priseurs, 5 Rue Drouot, room 3, 1st floor. Objects also taken to Paris by Consul Alby’s nephew in 1863? The sale was made in cash and the auction house took an additional commission of 5% on the sale price. The artefacts were: item 577, a torso statue of Apollo (18 cm) in marble of Paros; item 1050, a statue of Aphrodite (14 cm) sitting on a swan with a veil floating in the wind on top of her hair; item 1097, a statue of a standing Telesphorus (12,5 cm) wrapped up in a cuculus and previously featuring a phallus that was broken. The catalogue says that this last statue looks like a Telesphorus bronze kept at the Thordvalsen Museum in Copenhagen. I found an old drawing of the statue as the museum seems not to have it in its collection online. From Wikipedia, “Telesphorus was a son of Asclepius. He frequently accompanied his sister, Hygieia. He was a dwarf whose head was always covered with a cowl hood or cap. He symbolized recovery from illness, as his name means “the accomplisher” or “bringer of completion” in Greek. Representations of him are found mainly in Anatolia and along the Danube.” And on Anafi, one may add. (P. Pepe’s research.)